鲜花( 152)  鸡蛋( 1)

|

楼主 |

发表于 2016-11-29 09:45

|

显示全部楼层

本帖最后由 billzhao 于 2016-11-29 11:12 编辑

0 p& Q- C" `4 }$ J5 Y. k+ F" E: Q1 S# H5 ^# i1 |& k) o: w

A History Of Exclusion

- b) T8 P. L/ r3 v% F3 U) \$ {/ y" K* T/ }

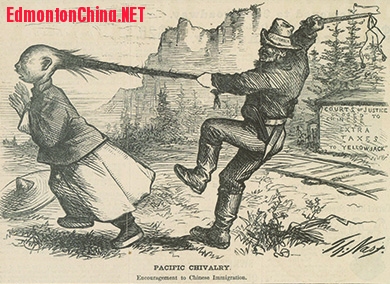

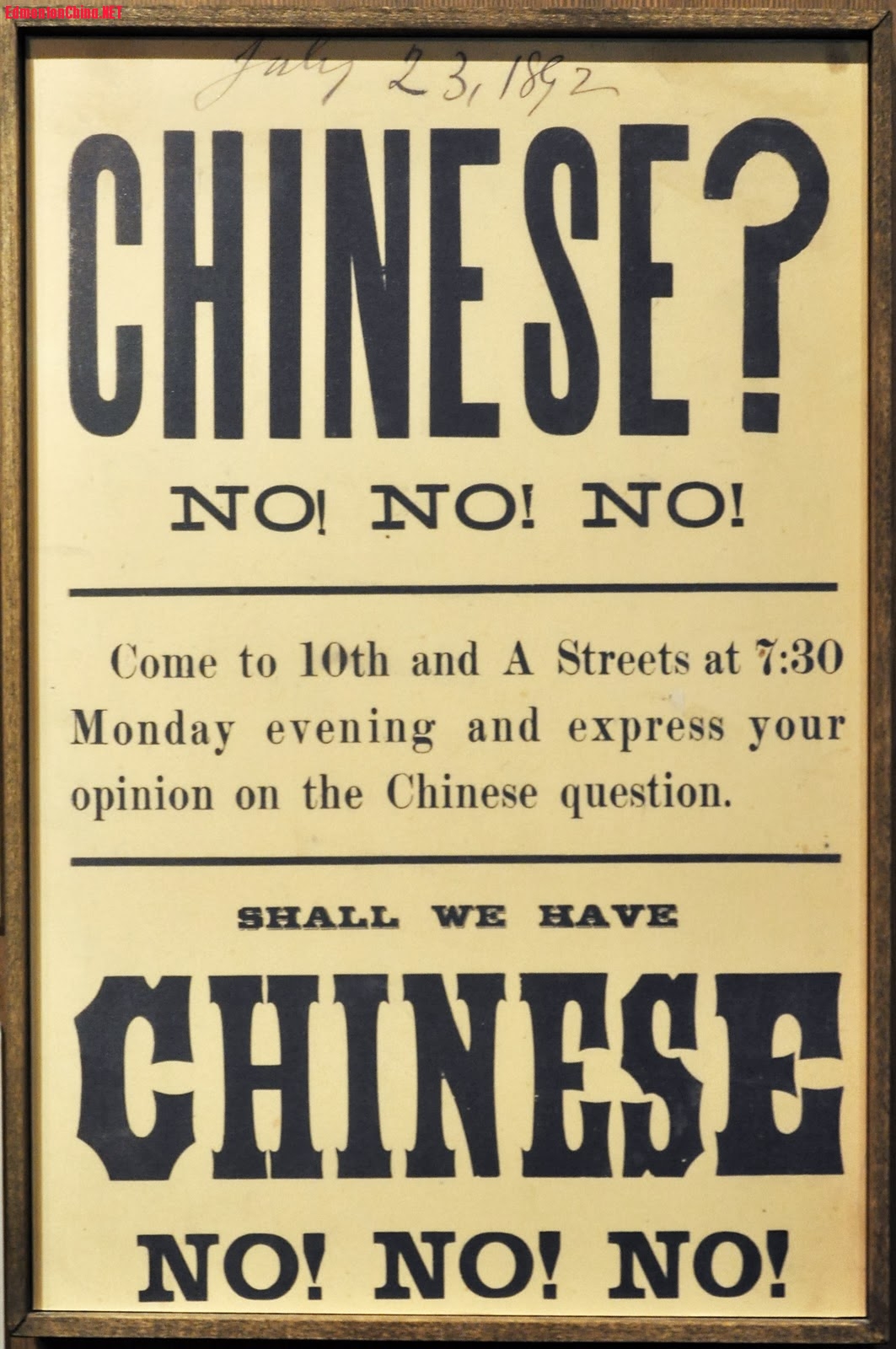

They have been in Canada 150 years, but for much of this time Chinese Canadians were unwelcome in this country. It started in 1885 when the Canadian government imposed a Head Tax on all Chinese immigrants entering Canada. By 1923, the government intensified its anti-Chinese efforts by making it virtually impossible for Chinese people to immigrate to Canada. This period of exclusion and legislated racism lasted until 1947. No other ethnic group was targeted in this way. Why did the federal government take such severe actions against Chinese people? To understand the motivation behind these discriminatory acts, it is necessary to trace the arrival of the Chinese in Canada.3 x% G" \4 v4 |& S ^0 c2 T6 K

+ d9 ^: U1 @5 O* ^" rFraser River Gold Rushes

+ `3 |/ _% D2 |" }/ l

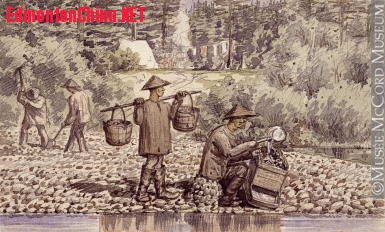

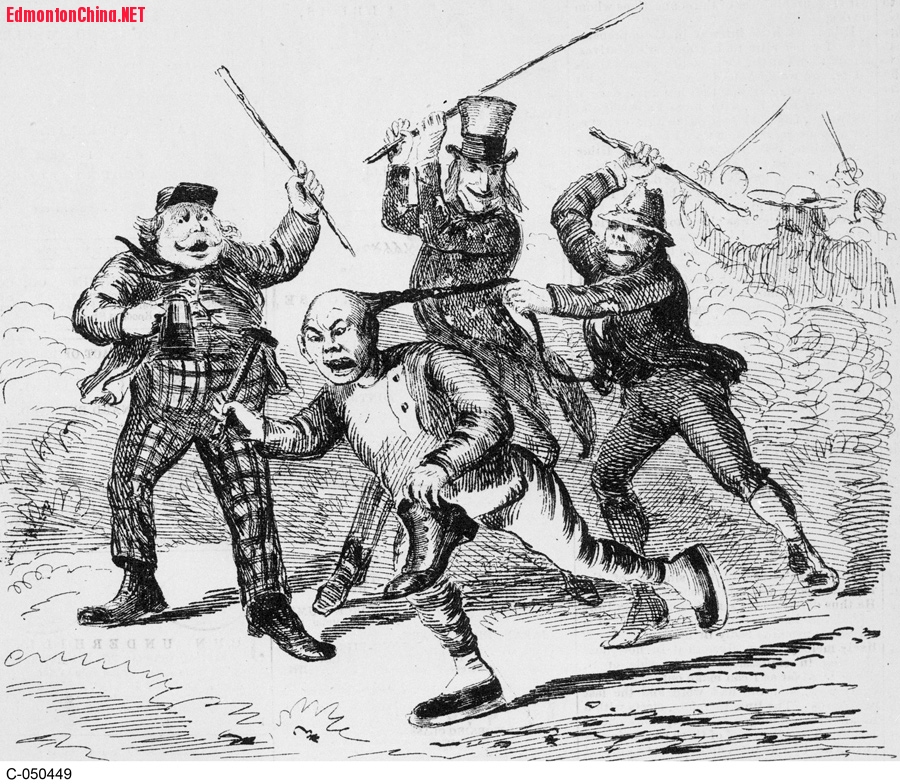

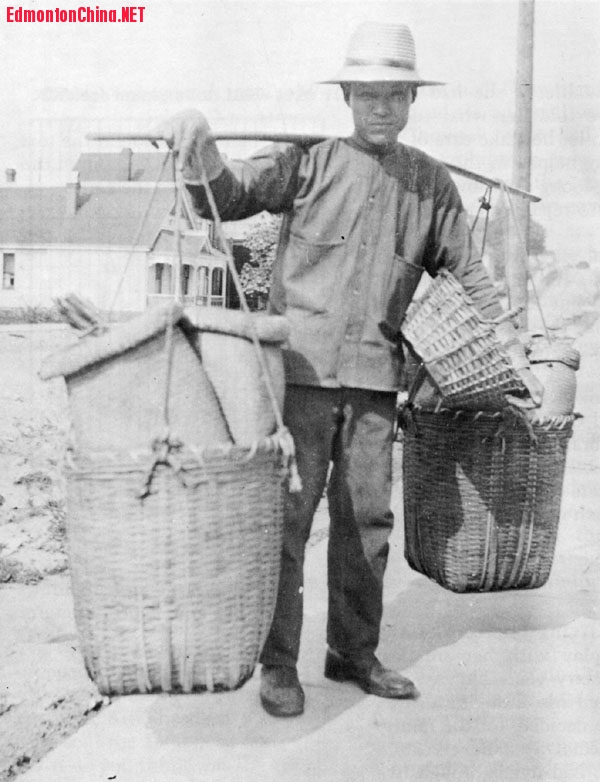

4 `! b# T0 z8 a" e: P2 {Gold was discovered in the lower Fraser Valley in 1857. In the following year, thousands of miners joined the gold rush in B.C. (British Columbia). The first group of Chinese immigrants from San Francisco arrived in Victoria by boat in June 1858. Soon after, more Chinese labourers came directly from Hong Kong to seek a better livelihood in Gum Shan (the “Gold Mountain”). During the pioneer days, shortage of labour forced the colonial government to rely on Chinese contractors for recruitment of Chinese labourers to build trails and wagon roads, drain swamps, dig ditches and engage in other sorts of backbreaking tasks. The prosperous period of the gold rush was basically over by 1865 and B.C. faced adverse economic conditions. A growing number of unemployed White workers began to blame the Chinese for taking away their jobs because of their willingness to work longer hours for lower wages. Hostility directed against Chinese immigrants emerged in B.C. in the late 1860s and burgeoned in the early 1870s.

1 {$ |; T/ R% z* h( D& H% _: ]& ~7 r5 v( [

/ S; o6 e3 M, @# \- N; k3 `

% p4 P; q7 c! y* }" A0 |7 [9 e1872 Disenfranchisement

- R* J0 u- h1 T' H B3 u! U. l/ r+ X) j' G

B.C. entered Confederation in 1871. In the following year, the first Legislative Assembly passed an act to disenfranchise Native Indians and Chinese. Cities and municipalities in B.C. followed suit to disenfranchise the Chinese from elections. From the 1870s onward, discrimination against the Chinese became a hallmark of the White citizens of B.C. The 1881 Census of Canada listed 4,383 Chinese in Canada of which 4,350 resided in B.C., 22 in Ontario, 7 in Quebec, and 4 in Manitoba. Before the 1900s, virtually all Chinese in Canada were concentrated in B.C. Hence, the province had the strongest anti-Chinese movement." x2 c. e6 w5 S8 t& p6 S$ _

9 W6 x; U% h# ^# u+ _ @

: B' \" {" q2 g+ \/ \- t2 i

: B' \" {" q2 g+ \/ \- t2 i

8 g0 ^4 k! V/ {" K

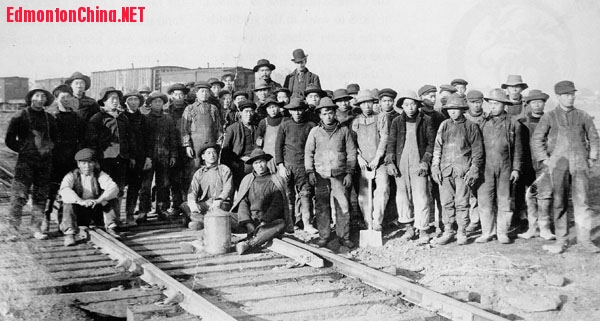

1881 Railway Construction2 ^4 e0 b, x7 C; L- P3 E

% C4 ]9 X8 `4 H& r

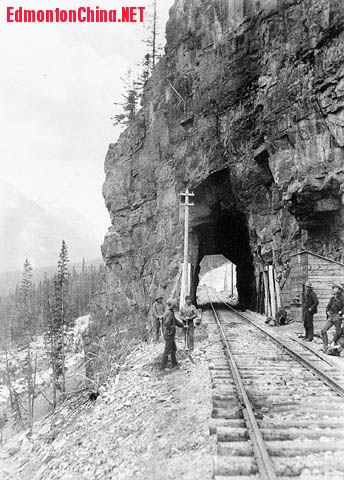

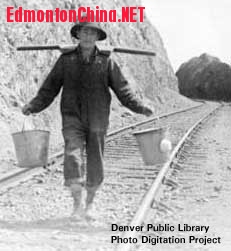

In 1879, Noah Shakespeare, President of the Workingmen's Protection Association (later known as the Anti-Chinese Association) organized a petition to the Federal Government, requesting that “Mongolian labour” should not be used on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in B.C. Andrew Onderdonk got the contracts to build the line and would need at least 10,000 workers. In 1880, the White population of B.C. was estimated at about 35,000, and most of them were engaged in gold mining, coal mining, fish canning or commerce. It was estimated that no more than 400 White men were available for employment on the railway. Hence, in May 1882 Prime Minister John A. Macdonald told the people in B.C. that “If you wish to have the railway finished within any reasonable time, there must be no such step against Chinese labour. At present, it is simply a question of alternative – either you must have this labour or you cannot have the railway.” Although many White Canadians deeply resented the Chinese labourers, failure to complete the railway was unthinkable. As a result, they had to choose the lesser of the two “evils,” and tolerate the employment of the Chinese. By the end of 1882, of the 9,000 railway workers, 6,500 were Chinese. Hundreds of Chinese railway workers died due to accidents, winter cold, illness and malnutrition.

; P }6 f, `# z

" w* l4 k( m0 s3 f ]

4 m; k/ F" a) X" ]% N

4 m; k/ F" a) X" ]% N

4 {1 z+ `6 d" T8 g

+ m" k! m" d0 A( C4 r6 S

+ m" k! m" d0 A( C4 r6 S

6 F- Z3 R1 o( R" P0 |: v

Head Tax3 V/ l/ _- f1 A0 y! S& l% q% f

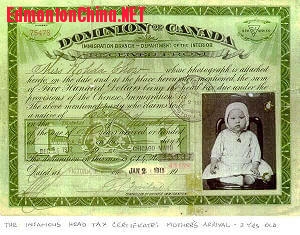

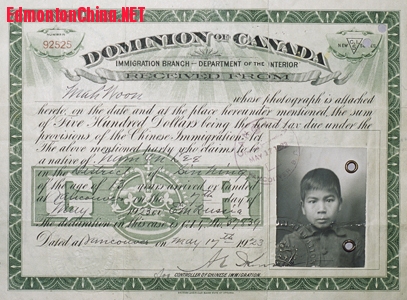

9 Y# {+ c2 T3 U& ^2 pIn 1885, the Federal Government, under pressure from the B.C. Government, imposed a head tax of $50 on every Chinese immigrant. Only six classes of person were exempt: diplomats, clergymen, merchants, students, tourists and men of science. In those days, the average Chinese labourer could earn only $225 a year. After deducting food, clothing, rent, medicine and other expenses, he could save only $43 a year. The intention of the head tax was to discourage Chinese labourers from coming to Canada by imposing a heavy financial burden on them. The tax was increased to $100 in 1901 and again to $500 in 1903. Despite the heavy tax, Chinese labourers continued to come as they were unemployed or could earn only $2 a month in China whereas they could earn from 10 to 20 times more in Canada. In those days, there was no immigration office in Hong Kong where nearly all Chinese came from. When a ship, usually carrying a hundred or more Chinese passengers, arrived in Victoria, they were lined up on the wharf and escorted to the prison-like immigration office. They were subjected to medical examination and then checked to determine whether they could pay the head tax, and if not they had to wait for relatives or friends to come to pay their taxes. This process could take several days or even weeks, and during this time, the Chinese immigrants were confined to rooms where all openings were covered with iron screens and bars to prevent their escape. They carved or wrote Chinese verses on the walls to express their anger and bitter feelings. One poem reads “Having amassed several hundred dollars, I left my native home for a foreign land. To my surprise, I was kept inside a prison cell! I can see neither the world outside nor my dear parents. When I think of them, tears begin to stream down. To whom can I confide my mournful sorrow.” V G, y* I7 d8 x( O6 |. r

2 R% x! ]1 s, h+ P5 u3 g

7 C, f5 H8 \; K

7 C, f5 H8 \; K

2 ~2 G- E) p9 ~, W/ Z+ n9 G

" ^" g; i. p1 k1 J/ f* _ S; @Exclusion. J' H8 v r9 G

; u. L% [7 O( {

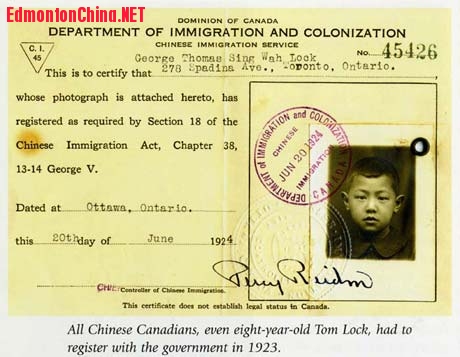

As head taxes failed to curb Chinese immigration, the federal government passed an Act in 1923, by which no person of Chinese origin was permitted to enter Canada. During the period of exclusion from 1923 to 1947, many Chinese in Canada had to endure the hardship of separation from their family members in China. The 1941 Census reported that about 47% of Canada's 35,000 Chinese lived in 5 metropolitan cities: Vancouver (7,880), Victoria (3,435), Toronto (2,559), Montreal (1,865), and Winnipeg (762). Over 90% of the metropolitan Chinese population resided in and near Chinatowns. Chinese immigrants had come mainly from 8 counties on the western side of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong Province: 66% from Siyi (Four Counties), 16% from Sanyi (Three Counties), 9% from Zhongshan County, and the remaining 9% from various other counties

@: ?7 L% [8 v$ W0 w7 f0 d8 C

; h& e& M" |" U& V1 i& I

" p4 Z3 ^6 Z( \2 N4 i6 l$ @

" p4 Z3 ^6 Z( \2 N4 i6 l$ @

) a1 o H& s+ a6 W6 }4 k: ? }( W

) M+ `7 L& u$ d5 e9 @- `2 t3 F8 u7 Y1939 Unwanted Soldiers: G& y: {+ t7 G

) b5 I4 n, ^) K9 Q8 h: h/ r

After the outbreak of the European War in September 1939, the governments of British Columbia and Saskatchewan strongly opposed enlisting Asians in the armed forces, fearing that they would demand to be enfranchised after the war. Despite opposition, many native-born Chinese youths volunteered for military service to prove their loyalty to Canada although they were not treated as Canadian soldiers. It was only after Japan entered the war that the British started recruiting Chinese Canadians to infiltrate and fight behind Japanese lines in China, Sarawak and Malaya. After they were finally granted entry into the Canadian armed forces, over 600 Chinese Canadians served in World War II. On 14 May 1947, the federal government repealed the Exclusion Act and subsequently other discriminatory laws against the Chinese. The 1962 immigration policy opened the door to Chinese immigration. As a result, new Chinese immigrants rose from 876 in 1962 to 5,178 in 1966.

- i2 a8 @* B+ [

5 y( e `+ W3 ]" g, s

2 s& o4 ^4 F5 o. |8 b- F9 a2 e+ | n6 A" d. C

1957 Political Participation! R+ S4 H K+ A

6 o4 w2 Z# Y" {& A" @Having obtained the franchise, the Chinese began to participate in politics. Chinese war veterans succeeded in becoming elected officials. These included Douglas Jung who was elected MP for Vancouver Centre in 1957 and George Ho Lem who became a Calgary City Councillor in 1959 and, subsequently, MLA for Calgary in 1975. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, many Chinese Canadians were elected as MPs, MLAs, Mayors and City Councillors. Dr. Vivienne Poy (1998-) and Dr. Lillian E. Dyck (2005-) are two Chinese Canadian senators, and Governor General Adrienne Clarkson (1999-2005), Dr. David Lam, Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia (1988-1995), Norman Kwong, L-G of Alberta (2005-2010), and Philip Lee, L-G of Manitoba (2009-) are all of Chinese ethnic origin. The three Chinese Canadian MPs are Michael Chong (2004-), Olivia Chow (2006-) and Alice Wong (2008-).) j# N- }3 h5 P2 u8 y* m

8 Z5 a& u9 W2 f" E

# Q5 p) F- D/ t9 b4 ~' \ ~

# Q5 p) F- D/ t9 b4 ~' \ ~

- D+ O: z6 B# J! K% \/ j5 d4 j1 z0 i7 ~+ r0 w* M+ d/ {+ D/ s" i) @+ ^" f" o

Universal Immigration Policy

' s' Z- p* h: S) @: L* G+ x& a( b6 w O$ b" R

The Federal Government introduced a liberalized immigration policy on 1 October 1967. It gave people around the world an equal opportunity for admission to Canada according to their education, occupational skills, and other criteria. Immigrants were identified by their country of last permanent residence and not by ethnic origin. After 1967, Chinese professional and skilled workers from many lands and cultures entered Canada. In 1986, the Investment Canada Act induced many Hong Kong and Taiwan investors and entrepreneurs to bring substantial capital to Canada. During the early 1990s, most Hong Kong immigrants to Canada were motivated by political uncertainty due to the transition back to Chinese rule. With Hong Kong's 1997 designation as a Special Administrative Region of China, fewer people left partly because they perceived the future as more certain. For example, 44,169 landed immigrants from Hong Kong and 7,411 from Taiwan in 1994 dropped to 2,857 and 3,511 respectively by the year 2000. On the other hand, landed immigrants from China increased from 12,486 in 1994 to 36,718 in 2000. The number continued to rise throughout the 2000s. For example, within 5 years from 2001 to 2006, 190,000 immigrants came from China whereas only 103,000 immigrants came from Hong Kong. The 2006 inter-census reported that nearly 86% of 1,346,510 Chinese in Canada lived in 5 Metropolitan Cities: Toronto (537,060), Vancouver (402,000), Montreal (82,665), Calgary (75,410), and Edmonton (53,670). Today less than 40% of Chinese in Canada have come from the traditional counties on the Pearl River Delta while over 60% have come from other provinces of China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Vietnam and other parts of the world.

6 G5 o8 Y& g/ a7 Q

3 g9 n; ~% T- ^% Y7 E- J

: W# n: `8 x/ i v- \& FApology and Recognition0 f* q9 \9 \0 X$ K3 f1 j. k6 X1 L

# [; ?6 ?6 N0 R$ X* R1 ?2 E% n9 `/ \

On 16 June 1980, Parliament passed a motion recognizing “the contribution made to the Canadian mosaic and culture by the people of Chinese background.” This was the first official recognition of Chinese railway workers. In September 1982, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada installed a bronze plaque at Yale Museum, British Columbia, in honour of Chinese railway workers. In June 1986, four Canadian labour unions erected a cairn in the Chinese and Japanese Cemetery in Cumberland and dedicated it to Chinese and Japanese miners killed in coalmines. In 1987, all three political parties supported the introduction of an all-party parliamentary resolution to recognize the injustice and discrimination of the head tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act. On 22 June 2006, the Parliament of Canada issued an official apology for the historical mistreatment of Chinese in Canada

% n8 { Q! Q! j' k4 H" ~ |

|